As we come to the end of 2019 it’s not just the end of the year but also the end of a decade. So we thought it would be a good time to look back on what’s happened in the world of energy over the past 10 years and what consumers can expect for 2020 and beyond.

An increase in renewables

Back in 2010, Ireland’s level of renewable energy output was almost non-existent. Fast forward 10 years, and around 30% of our electricity is now generated from renewable energy - largely wind - which is the highest in Europe and marks a huge turnaround in such a short timeframe.

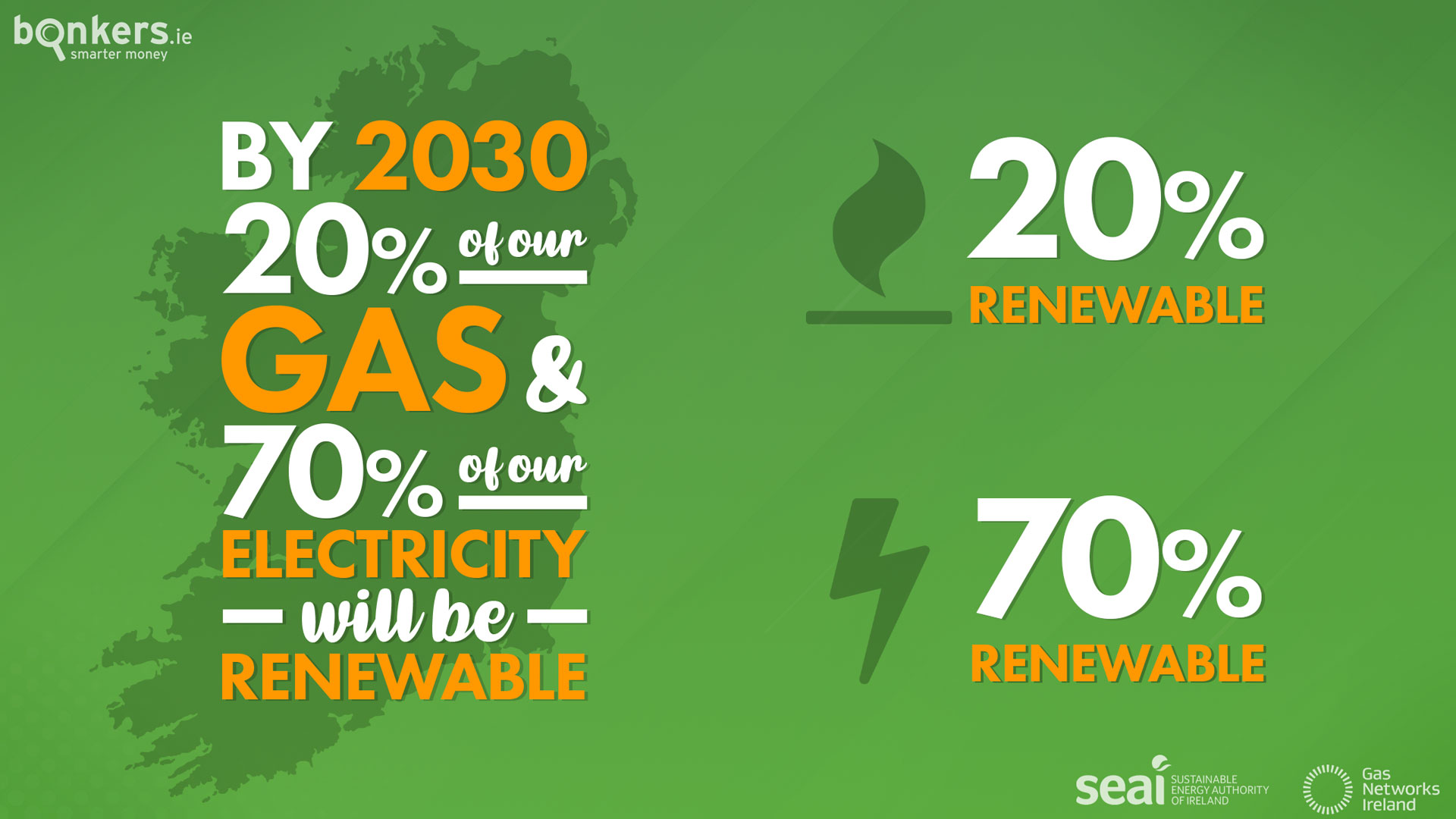

For 2030, Ireland has set a target of meeting 70% of our electricity output from renewable sources. And while investing in more wind farms will form a large part of that increase, other types of renewable energy such as solar energy and biofuels will become more and more important.

Many people scoff at the idea that Ireland can harness any significant energy from solar, given our notoriously damp and cloudy climate. But as solar technology has improved in recent years, it’s meant that even on cloudy days the sun is still strong enough, particularly in summer, to generate energy here. What's more, major energy suppliers like Energia and Iberdrola have announced plans for huge investments in renewable energy over the coming decade, with solar forming a key part of those plans.

Renewable gas will become a feature of our energy supply too. Renewable gas - also called biogas - is a direct substitute for natural gas. It comes from the methane produced by decomposing organic waste like animal manure, slurry, crop residuals and food waste. More importantly, it can replace heavily polluting fuels such as coal, oil and peat and it can be used in power generation, heating and transport.

Renewable gas is also relatively easy to store and is more flexible than wind or solar energy, as it can be produced in different quantities and at different periods.

In August, Gas Networks Ireland announced that it had injected farm-produced natural gas into the national network for the first time at a site in Co Kildare and by 2030 it’s projected that 20% of Ireland’s gas supply will be renewable.

As a result, the '20s will see far more wind farms, solar panels and biogas facilities gracing fields up and down the country and a gas and electricity supply that’s increasingly green and clean.

The end of peat

Burning peat is bad for two reasons. Firstly it’s extremely polluting - more so than coal in fact - yet it generates less energy than other fossil fuels when burned. As a result, it's one of the worst fuels, from a climate and environment point of view, to use for heating your home or generating electricity.

Secondly, bogs, much like the sea, act as huge carbon sinks by naturally trapping and storing carbon dioxide. So when you harvest bogs, you’re destroying some of the earth’s natural ability to store the greenhouse gas.

As a result, the writing has been on the wall for peat production in Ireland for some time and the '20s should see peat practically cease to exist as a fuel source in Ireland.

The ESB-owned peat power plants at Shannonbridge in Co Offaly and Lanesborough, Co Longford, are to close at the end of 2020 while Bord na Móna is to exit peat production by 2025, leading to the closure of 21 bogs across the midlands.

The end of the PSO levy?

The PSO levy was introduced in 2010 with two main objectives: to support the renewable energy sector and also support indigenous sources of energy supply, namely peat.

With the renewable energy sector beginning to thrive and peat gradually being phased out of use, the need for the levy, in theory, will become smaller and smaller.

Already we’ve seen the levy fall from a high of over €100 a year three years ago to just under €39 a year at present.

Could the next decade see its need disappear altogether, giving households a small reprieve from ever-increasing energy bills?

An increase in the carbon tax

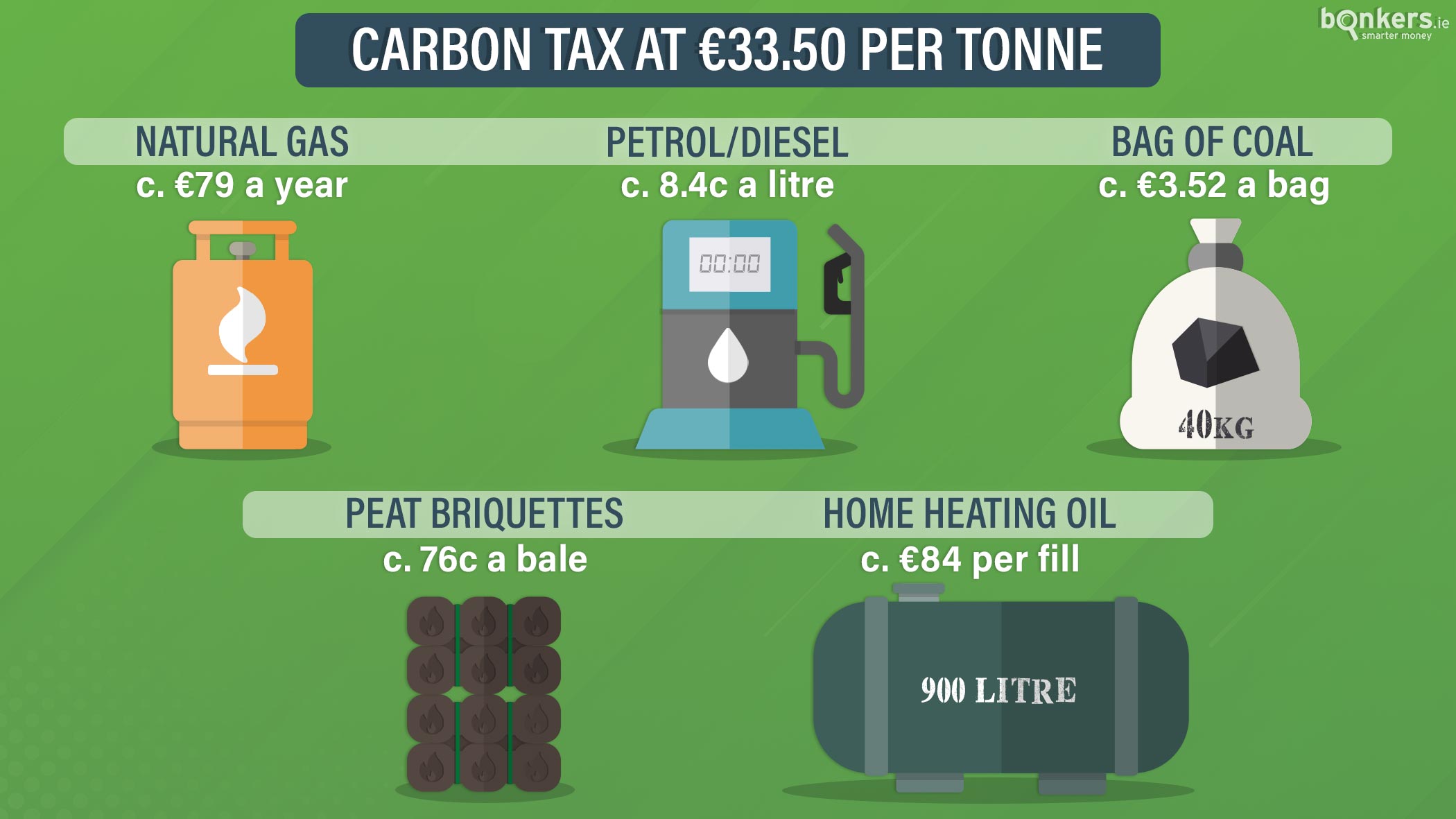

One levy we definitely won't see the end of is the carbon tax. First introduced in 2010, the carbon tax is applied to carbon-emitting fuels such as coal, peat, oil and natural gas. The tax is intended to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and is part of Ireland’s strategy to support a greener and cleaner environment.

The charge is currently €26 per tonne of CO2 emitted by the fuel concerned, meaning more polluting fuels are taxed more. However many environmental campaigners have called for the tax to be increased significantly and the Government has set a target of €80 per tonne by 2030.

However according to the ESRI, the real cost of carbon, if accounting for its warming impact, is likely somewhere in the range of €150-€200 per tonne, which, if implemented, would drastically increase our gas, driving and heating costs.

Regardless of the trajectory that’s decided upon, the tax is only going one way over the next decade.

Households generating their own electricity

Households generating their own electricity should also become a mainstay feature of the Irish energy market over the next decade. This will come mainly in the form of solar panels.

Under the Solar PV scheme administered by the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) homeowners can currently avail of a grant of up to €3,800 to install solar electricity panels on the roofs of their homes or in their gardens to generate their own renewable energy for running their home.

The SEAI estimates that, on average, a solar PV system can save a household between €200-€300 a year on their electricity bill.

However the real savings could come by allowing households which generate excess electricity to sell it back to the national grid.

Under the Government’s recently announced Climate Action Plan, a new Microgeneration Scheme is to be established which would allow homeowners who generate their own renewable electricity to sell back any extra energy they don’t use. According to industry experts, this could result in payouts of up to €400 a year.

So expect to see solar panels gracing the roofs of far more homes by 2030.

A world of electric cars

It seems like any sci-fi film from the ‘70s onwards seemed to portray the future as a world with flying cars. And while that prediction certainly hasn’t come to pass, a world of electric cars seems entirely realistic over the next decade.

The transition won't come overnight, as despite the grants currently available, the upfront cost of electric cars is still prohibitively expensive for many people. The lack of charging points nationwide is also a huge issue. But despite all this, the trend towards the electrification of our cars and also our transport fleet seems inevitable, which will be good for the environment as well as our our pockets.

For example if you were making a 425km return trip to Galway it would cost you around €34 in a petrol car and €26 in a diesel car, based on an efficient 5.5 litres per 100km for petrol vehicles and 4.6 litres per 100km for diesel, and a price of €1.34 a litre for diesel and €1.45 a litre for petrol. But according to the ESB, 425KM would cost just €5.39 in a Nissan Leaf – based on home charging costs using night rate electricity.

Not bad!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)